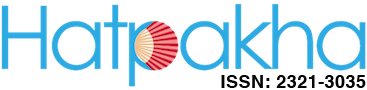

Animesh sat on the big wooden chair in front of the roadside shop of Dorji Sonam. He had walked enough. That afternoon he took a different route through the helipad of the nearby army base for his evening walk. He was too tired. The shop cum residence of Dorji Sonam was the only habitable house on that part of the roadside. There were at least a dozen of prayer flags, fluttering in the wind on either side of the road. There were two more small houses; each one was housing big wooden prayer-drums with gorgeous Tibetan paintings all over and the pretty big inscriptions, ‘Om Manipadme Hum’ across those prayer-drums. As you rotate those well-decorated prayer-drums, some adroit-fittings placed within, in such a way that a striking bell would produce a sweet and melodious ‘ding-dong’. They used to chant their seemingly unending prayers, which were quite close to their heart and rotate the drums before they set out to trek the hilly paths to their distant-destinations and also when they would return the said road-point after a tedious hitchhike as well. Three such distant small hamlets, amidst the picturesque background were visible from there. That small place on the roadside was at the far end of a large S-like turn of the serpentine main road, the only link with the outside world. There were a few massive Magnolia trees, which Animesh liked very much especially when they were in full bloom.

They called that forbidden road-point, the bus-stand of Gerdaangpaa, while the army personnel of the nearby joint-check-post called Indiraa-point. Initially Animesh could not understand why they called so. Only about a month ago Adm. J.C.O. Mr. Nair told him that long back the said name was jovially given by an N.C.O. after Dorji Sonam’s mother. Animesh had not seen her. She was no more by then. She used to sit like a statue right in front of the shop. The said old lady had an exceptionally long nose, which off course an unerringly rare feature among the hill-folk out there.

Animesh took out the packet of tobacco, the small pack that contained paper-strips and started making a cigarette. While doing so he looked for the shopkeeper, Mr. Dorji Sonam. Perhaps he was out of station for buying articles for his shop from the town on the plains. That place on the plains with market, hotels and crowd was too far from the said road-point, the bus-stand of Gerdaangpaa and the hill-station named Womdong where Animesh was working as a resource-teacher for the local government school. The journey to that said town would take a long & tiring ten hours by bus. A private vehicle would reduce the tedium about three hours. Any way Animesh was in a good mood and wanted to talk with the bulky loquacious Dorji Sonam. Like others he would also address him Aataa Sonam. Animesh found him very interesting. He was the only convivial man among the few locals with whom he could talk about many things.

While smoking the newly-made-cigarette he heard the distant sound of the approaching bus, the same one that one day would carry him out of those God-forbidden hills back to the plains. The mere sight of the bus would buoy up his confidence and help to combat his hill-sickness. After a few minutes, it came and halted at Gerdaangpaa. The shopkeeper Dorji Sonam got down. They exchanged a few words. Sonam greeted him and told him that he had brought his favourite brand of cigarette. Animesh was introduced to a middle-aged man from the plains with grey bushy mustache, one Mr. Thakur by Dorji Sonam. Mr. Thakur was transferred from Gnadung government school to the school of Womdong. In reply of his usual quarries that most newly-transferred people do, Animesh informed him that the place though situated on quite a high altitude but not very far from the road, which was literally the life-line for the people working in that part of the world while the army CSD canteen, Langar the army eatery, club and hospital were indeed added advantages. There were other schools in such distant places where one has to reach trekking continuously for one to few days. And people were working in those schools as well. Such an experience for the people from the plains would be definitely inexplicable.

As the bus would go through the Womdong bus stop too Animesh boarded the bus and soon reached there. Mr. Thakur, his wife a frail and lean lady and their three children alighted along with their bag and baggage. Animesh observed the emaciated face of the lady through a few furtive glances. Showing the distant river Tshangmechhu deep down the hills, Animesh told them how the water would glint in the morning sun. By that time the sun was about to set. The western horizon turned bright red. The distant hills started disappearing and the silhouettes could be seen. When the bus left they could only listen the chirping of the birds returning to perch on the trees of the hillsides below the road. Since there were no one around who could help to carry their baggage they kept the luggage in a shop nearby for the time being and started walking towards Womdong. Next day some boys from the school were requested to carry Thakur sir’s baggage.

A few days passed. Animesh found that not only Mr. Thakur even his wife and children were quite conversant with the local dialect. ‘Thakur sir’ slowly became quite popular among the school children. He was putting up in a desolate house about a kilometer away from the school on the way to a local monastery in the valley of Saktengompaa. Animesh was invited thrice in his lonely house amidst the small valley of Saktengompaa. During these brief meetings Animesh became quite friendly with them. He would enjoy playing with the kids. He would take them to the nearby monastery. Slowly the kids became very fond of him. The youngest one would call him ‘Aanis-untel’ in his unique style of utterance.

One Saturday evening he had a rendezvous with the couple. The children were too tired by then. They were sleeping. One on the jaded mattress and the other two were diagonally lying opposite to each other on the lackluster bed. Mrs. Thakur was talking about many things. Most of that talk was about their varied experiences at various hill-stations. During that meeting she requested Animesh to watch out her husband for he had already developed the very bad habit of drinking. She proclaimed that initially it was occasional and mostly in a pretext of accompanying friends and acquaintances. Gradually those occasional parties became frequent. The number of pegs started increasing and finally addiction enslaved him in Toto. The jaded eyes & pallid face of that petite lady were the mute testimony of the melancholy she had had and the solicitude she had for her husband while the amicable nature of Mr. Thakur would please all his colleagues. Animesh also liked that zesty man. When sober he was indeed vivacious. He had a never-ending stock of jovial jokes and anecdotes.

One afternoon Animesh was relaxing at Tshomo aamaa’s shop. The shop of that lady was very near the school campus. Tshomo aamaa could communicate somehow in broken English and her shop wasn’t as dirty as the other ones. Thus, Animesh would sit in that shop. He observed that in that part of Eastern-Himalayas, they called Sherchokp hills; most of the shops were attended by their women-folk. It was bit chilly that day. He asked for a glass of hot-butter-tea, they called Sujaa. Meanwhile a lama, a Buddhist monk of the local monastery and two small girls entered. Tshomo aamaa bowed the lama and wished him saying something in their typical traditional manner. The young lama donning his bright yellow and maroon robes thanked her and smiled customarily looking at Animesh. Tshomo aamaa offered him a betel leaf, one half of a raw betel nut and a little lime; they called these three things together as ‘domaa’. Those two little girls attired traditionally with bright coloured ankle length dress tied at the waist with typical woven belts, bought a few pieces of hardened cheese, they called ‘churpi’ and whisked away in a nearby house.

Looking at the sky and the distant hills blankly Animesh started sipping the sujaa. Initially he didn’t like the beverage but slowly he started liking that salty-herbal-butter-tea, sujaa. While gazing outside he noticed someone at the far end of the narrow path, which led to Saktengompaa. It was difficult to make out whether that man was going up or coming down for he was literally swaying. Pointing her finger towards that man Tshomo aamaa said, “Look, there is Thakur sir; he drank a lot some time back at Karna’s shop.” Animesh did not say anything but took a deep breath. Every shopkeeper knew about his habit of drinking. He had an account, to buy things on credit, in almost every shop around the school campus wherever hard drinks available. On the pages of his accounts ‘rum’ was written more number of times than any other necessities. Once he jovially remarked, “Every time I go through my accounts I read and recall the name of my favourite God”. After finishing the sujaa Animesh called a loyal student of him and started walking towards Saktengompaa. They found him lying beside the path on a bed of profuse ferns near a small abandoned house. They dragged and somehow carried his body to his desolate house at Saktengompaa.

Next morning he was there in the school, sober and sound, as if nothing happened. Looking at him Animesh was dumbfounded. He wished he could rail at him with raucous diction. During the first half of that academic year Mr. Thakur repeated the similar episode at least ten different times. And every time the next morning he would delude his wife with false promises. Animesh requested all the shopkeepers not to sell liquor to him. Owner of the few shops, somewhat well to do ones did stop but the small and petty shopkeepers would still sell surreptitiously. Animesh was helpless. There was nothing he could do to stop that. He felt very sorry for the plight of Mrs. Thakur and the kids. Many people used to make fun of him including a few teachers. One Mr. Rodrigo would gibe anything in his utterly vulgar tongue quite frequently.

During the break after half yearly examination Mr. Thakur and his family went out of station boarding on an army vehicle all on a sudden. That was quite unexpected. Teachers working there on the hills normally would not prefer to go out during such short break of few days. Upon returning it was revealed that they had been to a pilgrimage. Henceforth, Mr. Thakur used to adorn his forehead with a tilak, an impeccable conspicuous vermilion mark. Every evening he would reach his house on time and perform puja everyday. There was a small temple in the campus of the army joint-check-post. He would visit that temple with his kids regularly. Except in school he was never found alone near the shops of Womdong. He would always come out with his family whether to shop or to visit the quarters of other teachers. The people of Womdong unbelievably witnessed the incredulous change of Mr. Thakur.

After a month or so, one afternoon the Thakur family invited Animesh to Saktengompaa. He was playing volleyball then with some students beside the school kitchen below the hillside of Tshomo aamaa’s shop, Mrs. Thakur sent a student to call him. The Thakurs came to shop around in that part of the so-called market area of Womdong.

Animesh donned the thick olive-green jacket, put the woolen muffler around the neck, took his torch and on the way he bought some good quality toffees. The sky was quite clear. There was bright and large full moon. The prayer-flags on the hillside above the house of Danglaa aapaa, the apple orchard below, the school quarters, shops and post office were all quite visible in that beautiful golden moonlight. Not a soul, not even a stray dog could be seen outside. There was a charming unknown wild odour in the air.

Upon reaching the house at Saktengompaa he found that Mr. Srivastava, another teacher was also invited. He was playing carom with Mr. Thakur’s kids. They were very much engrossed when Animesh climbed the wooden stairs. An aapsu, a much hairy small sized dog of Tibetan breed, was dozing on a small wooden platform below a well-blossomed peach tree nearby. Mrs. Thakur welcomed him with folded hands and said, “Namaste”. Animesh noticed during several instances that she used to speak chaste Hindi but in a different accent. Mr. Thakur was performing his evening puja. The chanting of Sanskrit verses was very much audible. Having finished the evening chore of his, Mr. Thakur came out of the small room and wished them in his typical style. He presented a few philosophical couplets in Hindi and translated those particularly for Animesh. They talked on some varied and unimportant matters. Mr. Srivastava said some interesting jokes in Hindi.

By then Mrs. Thakur started making a ‘drink’ with skilled precision in a quite big glass. She leaned forward to hand over the glass to her husband. While doing that she remained in sheer silence and threw a furtive glance towards the guests. Animesh noticed that and he can’t but literally taken aback.

Wearing a wry smile on her gaunt face she glanced at Animesh for a moment and went inside the kitchen to bring tea for the guests.